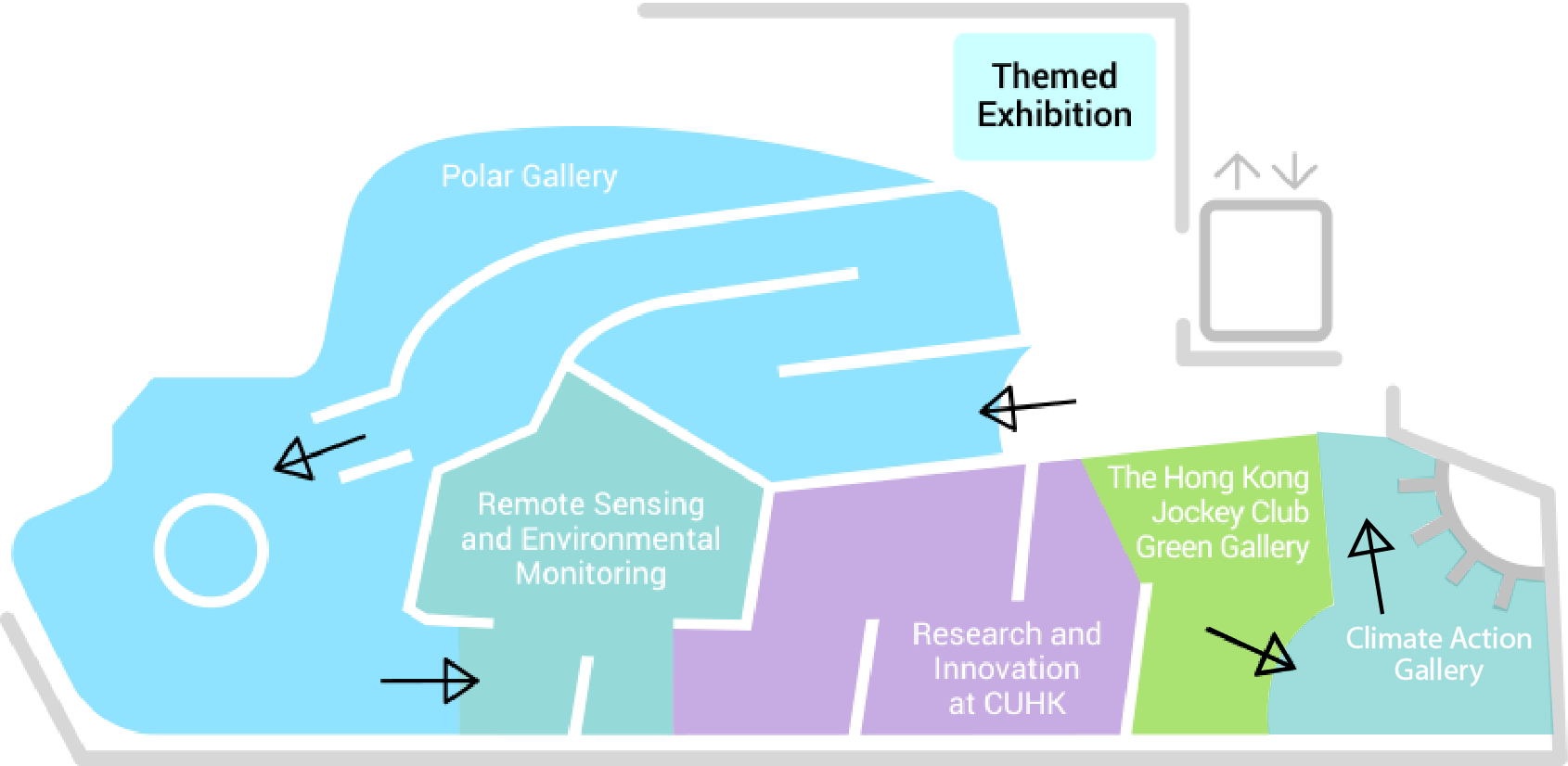

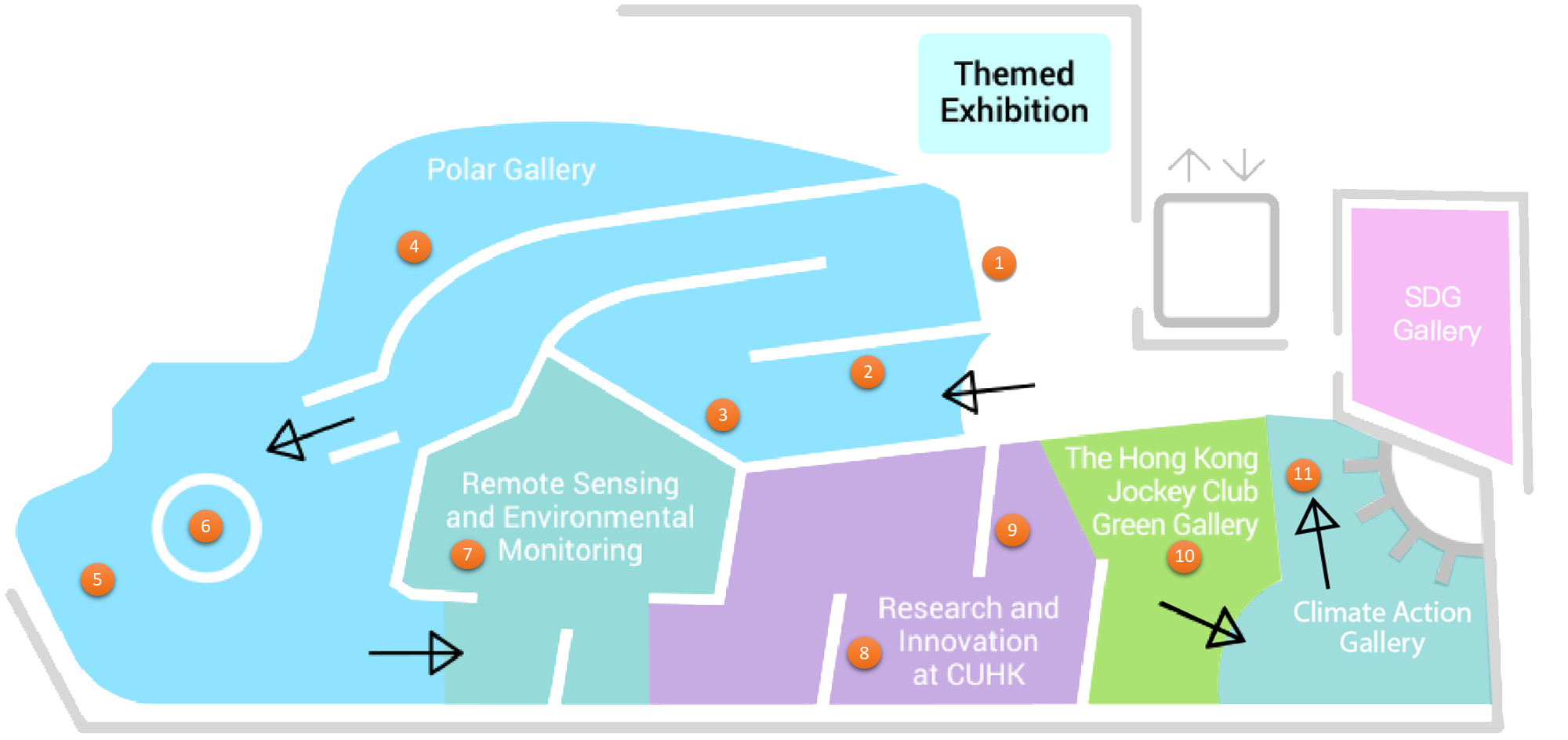

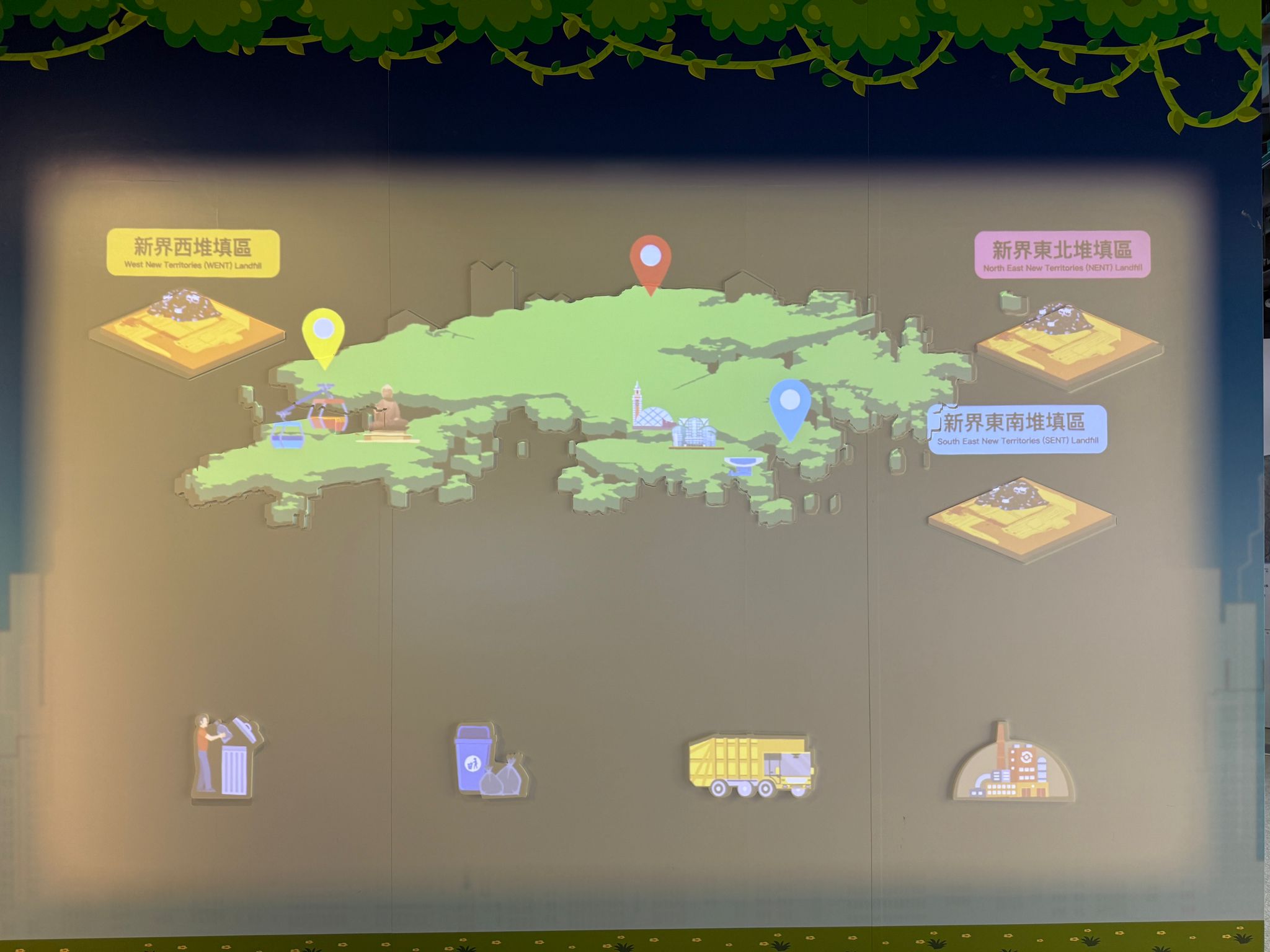

MUSEUM MAP

The CUHK Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change (MoCC) will launch the Mobile Exhibition “The Fading Colours of Coral” in October 2023, to showcase potential threats of climate change on marine ecology, with the aim of inspiring students to adopt new thinking and take practical action to address climate change.

Programme Details (Chinese version only)

![]()

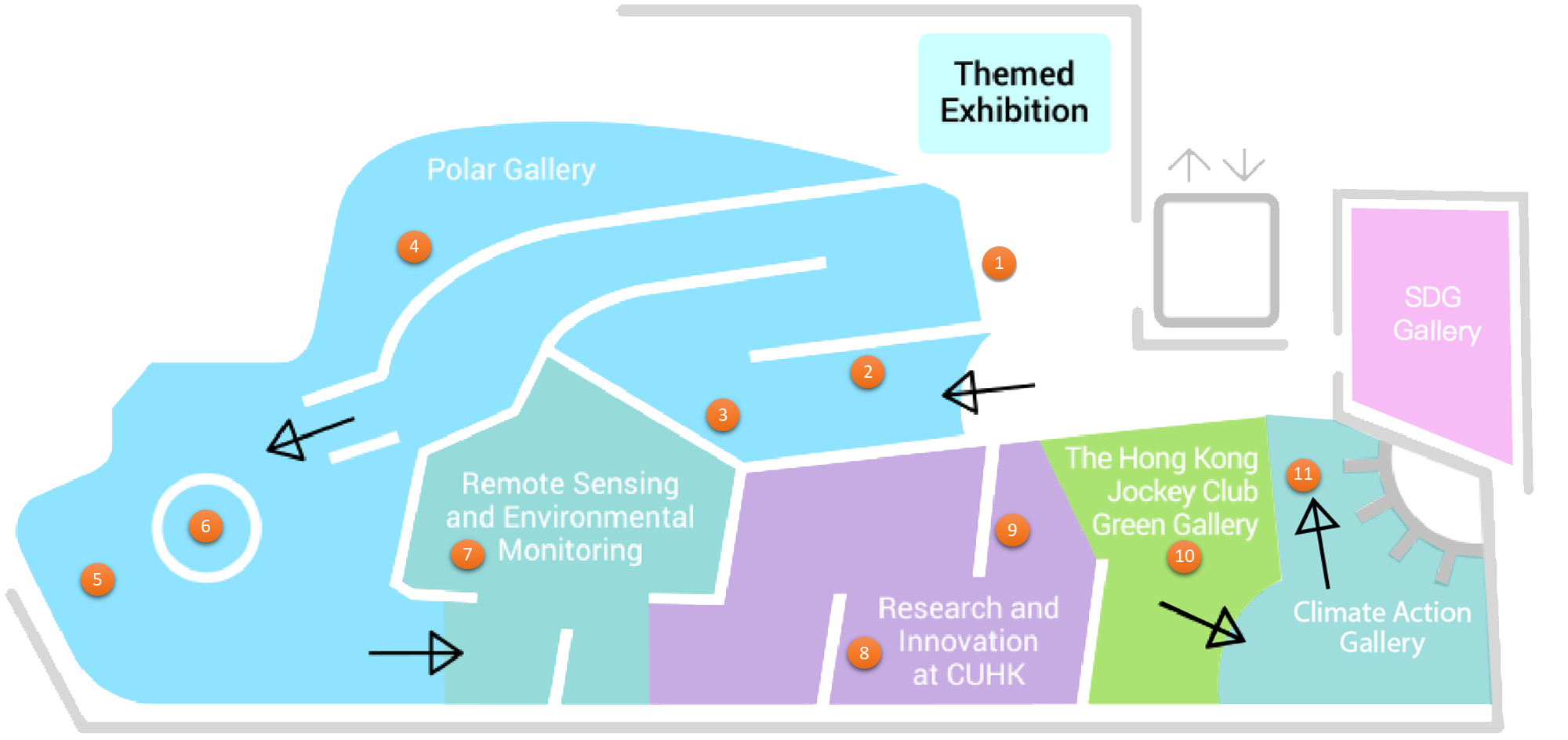

The exhibits in this section are based on the valuable collection from Dr Rebecca Lee, the renowned environmentalist and explorer, built through her lifelong fieldwork in the "Three Poles" (the North Pole, the South Pole and Mount Everest) and network with research institutes in mainland China. This collection offers a vivid demonstration to visitors on global warming and climate change, as well as the macroscopic impacts.

Remote Sensing and Environmental Monitoring is a collection of interactive multimedia presentation of the many types of environmental and climate information derived from Earth-orbiting satellites and other advanced technology. The visitors will be able to explore by themselves, through the application of geo-information science, how the Earth is changing in time and space and how climate change may impact the environment and their daily lives.

![]()

Research and Innovation at CUHK showcases the Chinese University’s innovative research results across a wide spectrum of environmental science and energy technology. Visitors are informed of not only the latest research developments and technological advances, but also the future potentials in these fields to combat climate change.

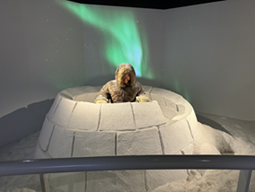

Environmental efforts require the community’s support. The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust has for years supported a significant number of projects to promote environmental protection in Hong Kong. This section presents major initiatives of the Club that have helped pioneer new thinking on how to protect the environment in the local community. With the aid of multimedia interactive exhibits, the exhibition promotes United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 12 – Responsible Consumption and Production – and aims to inspire the visitors to get involved in waste-reduction action and to live a green lifestyle.

When you use this mobile application, we will have record of your Domain Name Server address and the contents you have browsed. This information may be used by us for statistical purpose only.

Policy on Personal Data

For the University's policy on personal data, please visit http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/policy/pdo/en/

The Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (hereafter "the MoCC") built the MoCC Mobile App app as a Free app. This SERVICE is provided by the MoCC at no cost and is intended for use as is.

This page is used to inform visitors regarding our policies with the collection, use, and disclosure of Personal Information if anyone decided to use our Service.

If you choose to use our Service, then you agree to the collection and use of information in relation to this policy. The Personal Information that we collect is used for providing and improving the Service. We will not use or share your information with anyone except as described in this Privacy Policy.

The terms used in this Privacy Policy have the same meanings as in our Terms and Conditions, which is accessible at Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change Mobile App unless otherwise defined in this Privacy Policy.

Information Collection and Use

For a better experience, while using our Service, we may require you to provide us with certain personally identifiable information, including but not limited to Email Address, your Domain Name Server address and the pages you have visited. The information that we request will be retained by us and used as described in this privacy policy. For the University's policy on personal data, please click here.

The app does use third party services that may collect information used to identify you.

Link to privacy policy of third party service providers used by the app

Log Data

We want to inform you that whenever you use our Service, in a case of an error in the app we collect data and information (through third party products) on your phone called Log Data. This Log Data may include information such as your device Internet Protocol (“IP”) address, device name, operating system version, the configuration of the app when utilizing our Service, the time and date of your use of the Service, and other statistics.

Cookies

Cookies are files with a small amount of data that are commonly used as anonymous unique identifiers. These are sent to your browser from the websites that you visit and are stored on your device's internal memory.

This Service does not use these “cookies” explicitly. However, the app may use third party code and libraries that use “cookies” to collect information and improve their services. You have the option to either accept or refuse these cookies and know when a cookie is being sent to your device. If you choose to refuse our cookies, you may not be able to use some portions of this Service.

Service Providers

We may employ third-party companies and individuals due to the following reasons:

We want to inform users of this Service that these third parties have access to your Personal Information. The reason is to perform the tasks assigned to them on our behalf. However, they are obligated not to disclose or use the information for any other purpose.

Security

We value your trust in providing us your Personal Information, thus we are striving to use commercially acceptable means of protecting it. But remember that no method of transmission over the internet, or method of electronic storage is 100% secure and reliable, and we cannot guarantee its absolute security.

Links to Other Sites

This Service may contain links to other sites. If you click on a third-party link, you will be directed to that site. Note that these external sites are not operated by us. Therefore, we strongly advise you to review the Privacy Policy of these websites. We have no control over and assume no responsibility for the content, privacy policies, or practices of any third-party sites or services.

Changes to This Privacy Policy

We may update our Privacy Policy from time to time. Thus, you are advised to review this page periodically for any changes. We will notify you of any changes by posting the new Privacy Policy on this page. These changes are effective immediately after they are posted on this page.

Contact Us

If you have any questions or suggestions about our Privacy Policy, do not hesitate to contact us at mocc@cuhk.edu.hk.

收集個人資料聲明

我們會記錄使用本手機應用程式者的域名伺服器地址和曾瀏覽的內容,此等資料僅供統計之用。

個人資料政策

有關本校處理個人資料的政策,請瀏覽http://www.cuhk.edu.hk/policy/pdo/b5/

ECF ‘The Drama of Climate Change and a Low-carbon Future’

Funded by

Supported by the Environment and Conservation Fund (ECF), the two-year ECF ‘The Drama of Climate Change and a Low-carbon Future’ (the ECF project) aimed to educate the public, especially the younger generation, to embrace the importance of making green choices through themed exhibitions, ‘theatre-in-education’, a social media campaign and other experiential learning activities.

The objectives of this ECF project were:

which were achieved by the following five components:

Drama Tour

|

|

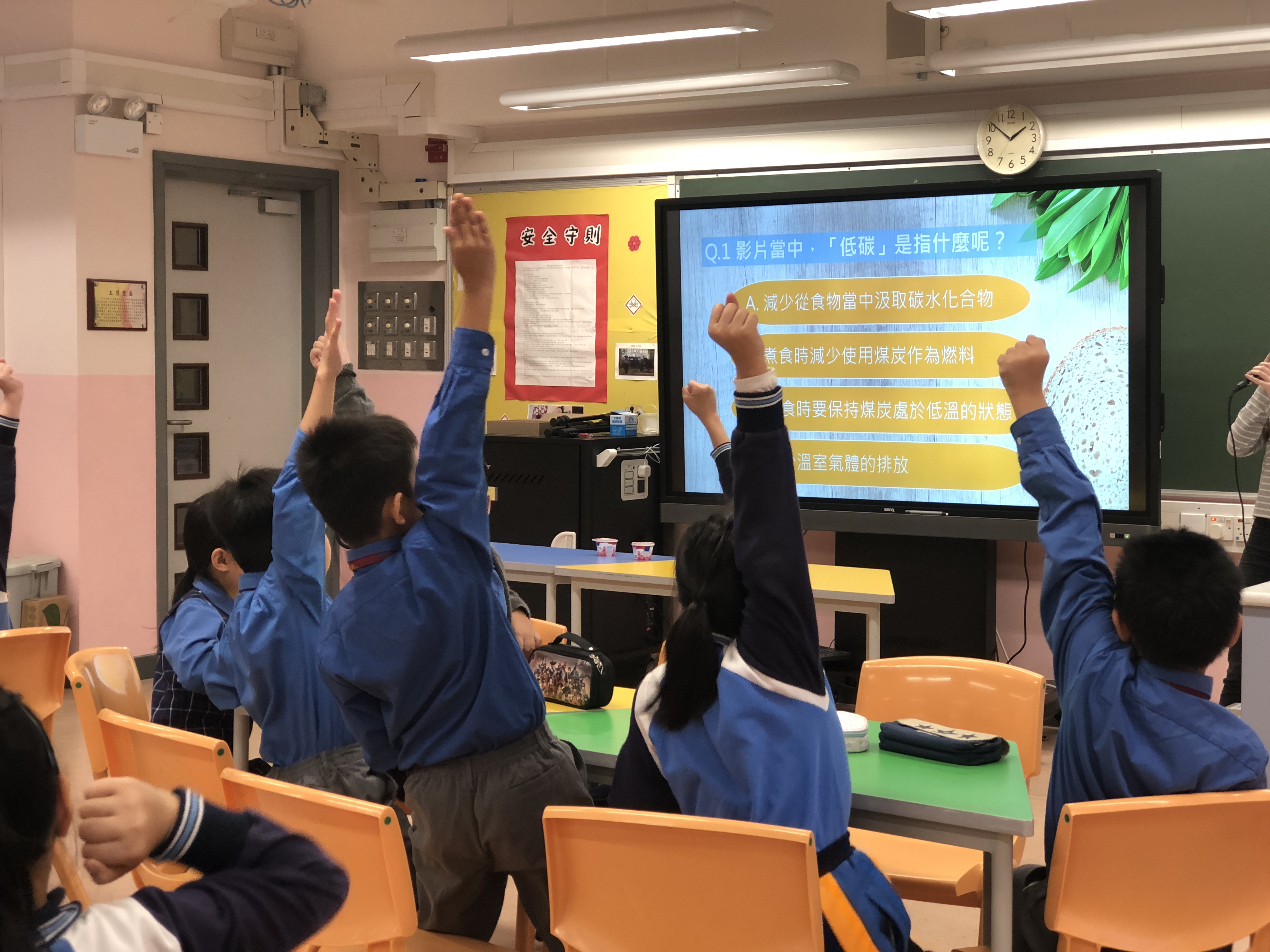

An educational drama in the theme of ‘Combating Climate Change: Towards a Low-carbon Future’ was produced by a professional theatre company with input from the scientific team of the Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change. Crafted with actor-audience interactions, the play appealed to young students and inspired them to adopt a more environmentally sustainable lifestyle to combat climate change. Premiered in September 2019, the play has been toured to 34 primary schools as at December 2019, reaching an audience of more than 9,700.

‘The Green Eaters’

The ECF project began with a fun yet, informative ‘The Green Eaters’ social media campaign, followed by the ‘Eating Greener’ exhibition (July to September 2019) at the Jockey Museum of Climate Change, to encourage the general public to increase their intake of plant-based meals, thereby reducing the carbon footprint of the carbon-heavy meat industry. The exhibition attracted close to 10,000 visitors.

Learn and Practise

|

|

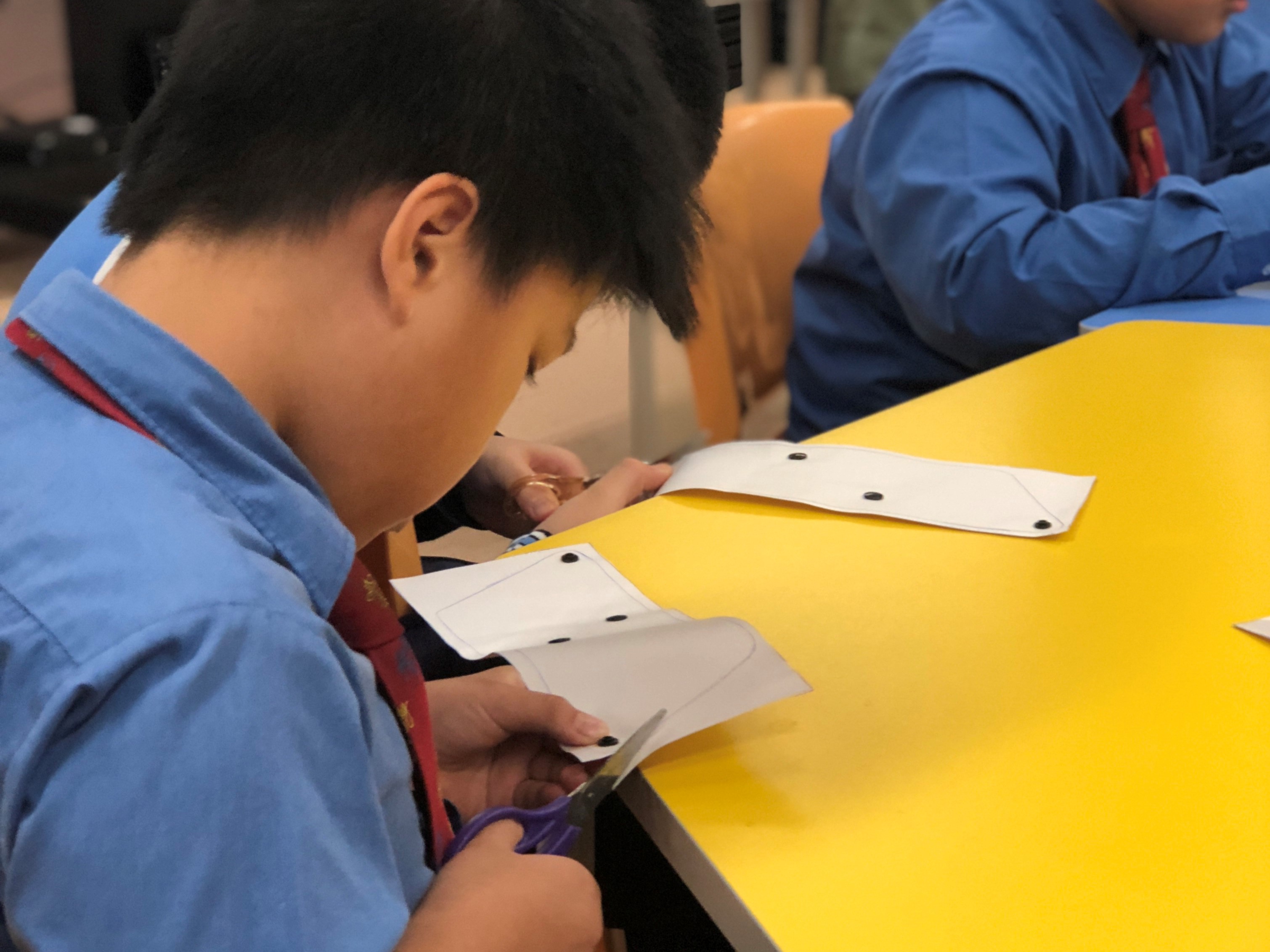

To complement and strengthen the primary school students’ knowledge gained from the drama, a series of ‘Learn and Practise’ activities are being carried out for the participating schools. The activities aim to convey a message to the students that they have the ability to change their own behaviour for the good of the planet and also influence their peers and family members to do the same.

GreeXperience@CUHK

|

|

To reinforce their understanding of climate change and low-carbon living, the students of the participating primary schools would acquire a special, first-hand green experience, or the ‘GreeXperience’, through environmental activities organized by the Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change. These activities include guided tours of the Museum and guided green tours on The Chinese University of Hong Kong campus.

‘Living Greener’ Virtual Exhibition

‘Living Greener’ virtual exhibition explores the relationship between everyday life and the global climate issues of today. It offers practical things we can do to incorporate sustainability into our daily life.

Enquiries: Richard Chung (3943 3979;richardchung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material/event do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Environment and Conservation Fund and the Environmental Campaign Committee.

Sustainable Development Goals Gallery

| ‘Sustainable Development Goals in Action’ Exhibition | ‘Small Actions, Big Impact’ Exhibition | |||

ECF Mobilizing Community Climate Action by Future Museum Curators

| Funded by | Supported by | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

ECF Mobilizing Community Climate Action by Future Museum Curators is an 18-month school-based community project supported by the Environment and Conservation Fund (ECF). The project capitalizes on the MoCC’s experience in climate outreach and advocacy and represents a unique model of experiential and problem-based learning through curating an exhibition that inspires community pro-climate actions. Student participants (our ‘Future Curators’) will have the opportunity to showcase their works at the MoCC and will reach a larger audience worldwide through our various global partners.

Objectives

Project Components

|

1. |

Training Future Curators |

|

The core component of this project is a comprehensive training programme designed to provide young people with the necessary knowledge and skills to communicate climate change and sustainable development through technology-aided exhibitions. |

|

|

Training Scope

|

|

|

Learning Outcome

|

|

Join us to help your students...

|

|

|

Enhance knowledge of climate change, science communication skills and innovative know-how Through a comprehensive training programme which includes sharing sessions, workshops and field trips, the programme participants (our ‘Future Curators’) will identify problems of climate change and explore the connections between climate change and the United Nations’ (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The training will be provided in multiple modules covering climate change knowledge, basic curation skills and the application of AR technology. |

|

|

Experience the work of a curator The programme will expose the participants to various aspects of a curator’s work, from content research, through description drafting, to exhibit design and development. Under the MoCC’s guidance, the participants will work with their teammates to curate their own exhibitions to be staged at their schools and in a virtual gallery. Selected curating teams will co-curate with the museum team a year-end themed exhibition to be staged at the MoCC. |

|

|

Showcase to the world The participants will have the opportunity to showcase their works to a larger worldwide audience through our global partners. These include:

|

|

|

Target Participants: S1 – S6 students |

|

|

Quota: 6 to 8 students from each school |

|

|

Award:

|

| The programme will consist of a series of interactive class and practical sessions. | |

|

Enrolment (by school)

|

|

|

School seminar

|

|

|

SDG 13 Keepers training (full-day)

|

|

|

InnoCurators museum operation training (full-day)

|

|

|

InnoCurators augmented reality training (full-day)

|

|

|

Future Curators’ exhibitions (brick-and-mortar)

|

|

|

Future Curators’ exhibitions (online)

|

|

|

MoCC exhibition (co-curated with the best-performing Future Curators)

|

|

| * Participating schools should complete the school seminar, the training sessions and Future Curators' exhibitions. |

|

2. |

Climate Action in the Community |

|

Various activities are designed to expand the reach and impact of the project, including:

|

|

|

|

Visiting green pioneers

|

|

|

A virtual gallery showcasing the exhibitions curated by the Future Curators

|

|

|

A themed exhibition at the MoCC

|

Enrolment

Secondary schools in Hong Kong are invited to submit their applications on or before 24 September 2021.

Applications will be selected on a first-come, first-served basis.

Apply online (In Chinese only)

Enquiries

Jennifer Cheng (3943 0817;jennifercheng@cuhk.edu.hk)

Disclaimer

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material/event do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Environment and Conservation Fund and the Environmental Campaign Committee.

Sustainable Development Goals Gallery

| ‘Sustainable Development Goals in Action’ Exhibition | ‘Small Actions, Big Impact’ Exhibition | |||

Test123

Test

| Application Forms | ||

| Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change: Guided Tour Service for Group Visits | online registraion | |

| Friends of the Museum (Individual Membership) Application | online registraion | |

| Friends of the Museum (Institutional Membership) Application | online registraion | |

| Registration for ‘CUHK–JC MoCC Alumni Association’ | online registraion | |

| Application for Hosting ‘Climate Change and Me’ Mobile Museum Exhibition | online registraion | |

Download our worksheet to bring more fun to science learning at the MoCC. The worksheet can be used in the classroom or as part of a pre-booked guided tour to the MoCC.

Download our resources to bring more fun to science learning at the MoCC. These resources can be used in the classroom or as part of a pre-booked guided tour to the MoCC.

Elementary level worksheets (suitable for primary school students)

Advanced level worksheet (suitable for secondary school students)

Please check out the Chinese version

Visitor Information

Exhibition Period: 22 March – 30 June 2018 (closed on Wednesdays, Sundays and public holidays)

Opening hours: 9:30 am – 5:00 pm

Venue: Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change, Yasumoto International Academic Park 8/F, CUHK (Near Exit D, MTR University Station)

Asia

Glaciers in Asia are known to many as the ‘Third Pole’ due to the fact that high mountains of Asia hold the largest frozen water outside the polar areas. They are an invaluable water resource, feeding many of the world’s great rivers, including the Ganges.

This water resource, however, is a risk under the current trend of global warming. Asian mountain glaciers will lose over one third of their mass by the end of this century as a result of global warming, affecting millions of people who rely on them for fresh water, a study finds.

Sabalan Glacier, Iran – Klaus Thymann (2014)

The glacier region of Sabalan rests on an inactive stratovolcano that rises to a height of 4,811 metres in the north-western part of Iran. The highest peaks of the mountains, known as Mount Sabalan, is a crater lake which is covered with ice from September through to June the next year.

Europe

Many of the glaciers in continental Europe develop on mountain ranges: The Alps, the Great Caucasus range, the Scandinavian mountains, Polar Ural and the Pyrenees. Glaciers on Iceland and Svalbard exist on lower altitudes, and exist due to their proximities to the North Pole.

The vast majority of glaciers in Europe are retreating. Those in the Alps have lost half of their volumes since 1900, with clear acceleration since the 1980s. Glacier retreat in Europe is expected to continue in the future.

Glacier Du Baoumet, France – Scott Conarroe (2015)

Sunrise shot of Glacier Du Baoumet. In places on the Alps, the borders of Switzerland, Italy, Austria and France are based on watershed. As global warming shrinks the glaciers, so does the watershed shift. The alpine landscapes no longer conform to borders established in the last century.

Esmarkbreen, Svalbard – Corey Arnold (2013)

The front of Esmarkbreen, a tidal glacier on the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard in the Arctic Ocean. The glacier was named Professor Jens Esmark (1763–1839), a Danish-Norwegian pioneer in glacial geology, who was the first to present convincing evidence for a glaciation in northern Europe.

South America

The glaciers in South America develop exclusively on the Andes; many on steep slopes and peaks above elevations of 5,000 metres. One of the most concerned region is the tropical Andes (Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia), where 99% of the world’s tropical glaciers occur. These tropical glaciers are regarded as among the most sensitive indicators of climate change on the planet, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Being a key aspect of the region’s water cycle, these glaciers have since the 1970s shrunk by 30–50%, an unprecedented rate in the past 300 years.

Mount Illimani, Bolivia – Klaus Thymann (2013)

Between the Pacific and the spine of the Andes, which curves through the southwest of the country, lies the vast, arid Andean Plateau. It is home to the city La Paz, and the grasses of the Altiplano Highlands of Bolivia. Further east, the grasslands and dry deserts give way to towering mountains and glaciers, and hidden by the forbidding Andean peaks is the Amazon basin.

Nestled within the Cordillera Real Range is La Paz, the world’s highest capital city at 3,640 metres above sea level. The city with a backdrop of peaks above 5,000 metres, including Mount Illimani, the second highest peak of Bolivia, is sustained by the glacial meltwater runoff. As glaciers recede the landlocked country is losing a vital resource that is not only used for water consumption but also contributes to forestry and agriculture, indigenous communities’ livelihood, and hydroelectric power generation.

North America

Glaciers in North America exist in both the United States and Canada, as well as in Greenland. Many of these glaciers are well monitored and designated as protected areas of National Parks in the United States and Canada. Albeit protected, many of these areas, if not all, are still affected by climate change. One of such areas are Mount Baker-Snoqualmie National Forest in the United States.

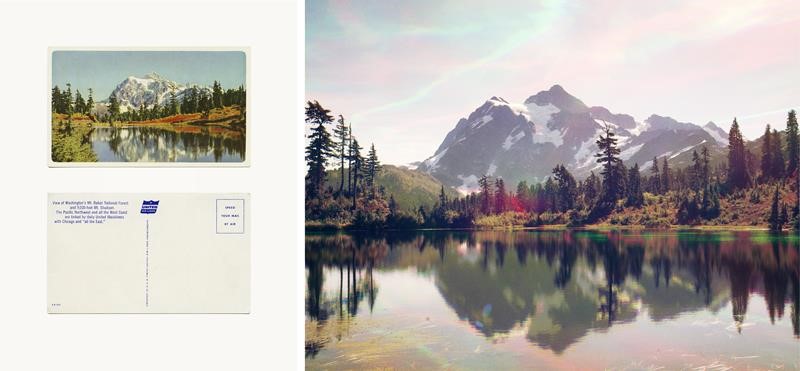

Mount Baker, USA – Peter Funch (2014)

Mount Baker, located in Washington State, USA, is a unique place where the effects of climate change can be seen from the accumulation of over a century’s worth of photographic documentation in tourist memorabilia. Following in the footsteps of Ansel Adams, Funch’s replica images of the existing collection of postcards and archival photography provide a decisive juxtaposition that highlights how the landscape has changed over time.

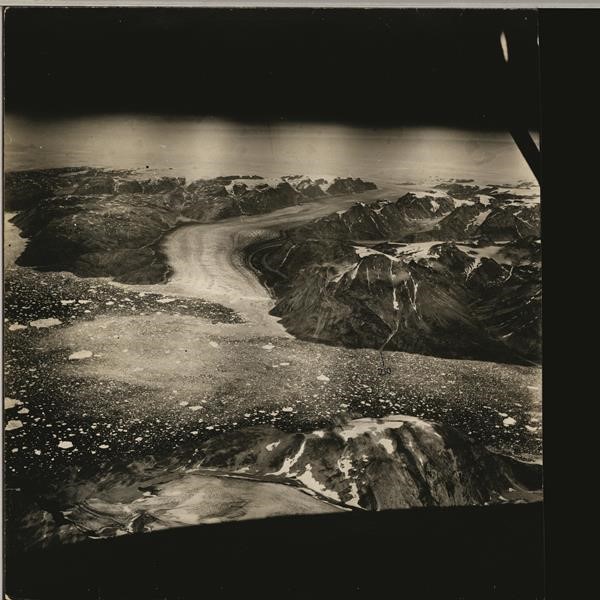

Helheim and Fenris Glaciers, Greenland – Klaus Thymann (2012) and Keld Milthers (1933)

In the early 20th Century, Denmark was in dispute with Norway over the sovereignty of eastern Greenland. To substantiate its claim, Denmark set forth expeditions to survey the remote region, including an aerial photograph survey by Danish explorer Keld Milthers in 1933. The aerial photographs, which were eventually rediscovered by Kurt Kjær of the Natural History Museum of Denmark in 2009, clearly outlined Greenland’s coasts, as well as the continent’s glaciers.

Collaborating with Kjær and the archive, Klaus Thymann revisited Helheim and Fenris Glaciers in East Greenland in 2012 to replicate the aerial photographs. The new photographs were taken same time of year as did Keld Milthers so that the historic and modern photographs can be compared directly. They demonstrate how the glaciers have retreated over 70 years.

Jakobshavn Glacier, Greenland – Klaus Thymann (2009)

Shot out of an open door on a hovering helicopter, the image shows the front of the Jakobshavn Glacier in Greenland. The wall is about 70 metres high. This glacier is among, if not the most, active in the world, producing some 10% of all of Greenland’s icebergs. The glacier moves forward at an average pace of 20 metres per day.

Africa

Resembling those in South America, glaciers in Africa are altitude related. Occurring in high mountains and close to the equator, they are very sensitive to temperature changes and therefore to global warming. Some believe that Africa is likely to be the first continent to be glacier-free due to climate change.

Lewis Glacier, Kenya – Simon Norfolk (2014)

Mount Kenya used to host many glaciers, this is no longer so. As a visual way of showing glacier retreat, Simon Norfolk used a self-made fire torch and a long exposure to demarcate the line to which a glacier once extended.

Mount Kenya is an extinct 5,199-metre volcano and this series intends to photographically re-awaken the mountain’s magma heart. The ‘Fire versus Ice’ metaphor is poignant owing to the trail of light being made from petroleum; the only evidence in these images that this glacier’s retreat is believed to be due to man-made climate change.

Speke Glacier, Uganda – Klaus Thymann (2012)

On the border of Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo, are the Rwenzori Mountains. This UNESCO-listed national park is home to six peaks above 4,600 metres, as the highest source of the Nile, they are also known as ‘The Mountains of the Moon’. Barely explored until the turn of the 20th Century it is estimated the glaciers will completely disappear within the next 15 years.

In 1906, there were 43 glaciers in the region; now only half remain and with a total coverage area of less than one square kilometre. The mountains are also home to 177 species of bird and mammals and an abundance of unusual flora. The tropical rains, high altitude and untouched landscape create conditions that encourages unique species to thrive. Thymann used a route that had lain unused for decades, after Congolese insurgents closed the park; through this route he discovered glaciers that were thought disappeared.

Australasia

No glacier exists in Australia. By contrast, there are as many as 3,000 glaciers in New Zealand. Many of them are located in the Southern Alps on the South Island and classified as mid-latitude mountain glaciers. They have been retreating since 1890.

When the glaciers retreat, some form proglacial lakes such the one shown in front of Donne Glacier, Mount Tutoko, New Zealand. Satellite imagery has revealed that many proglacial lakes in New Zealand are expanding in size due to glacier retreat.

Donne Glacier, New Zealand – Klaus Thymann (2013)

Top view of Donne Glacier, which descends down on the east face of Mount Tutoka, southwest New Zealand. This glacier has been undergoing rapid retreat for decades and in 2000 a new unnamed alpine lake was formed.

Antarctica

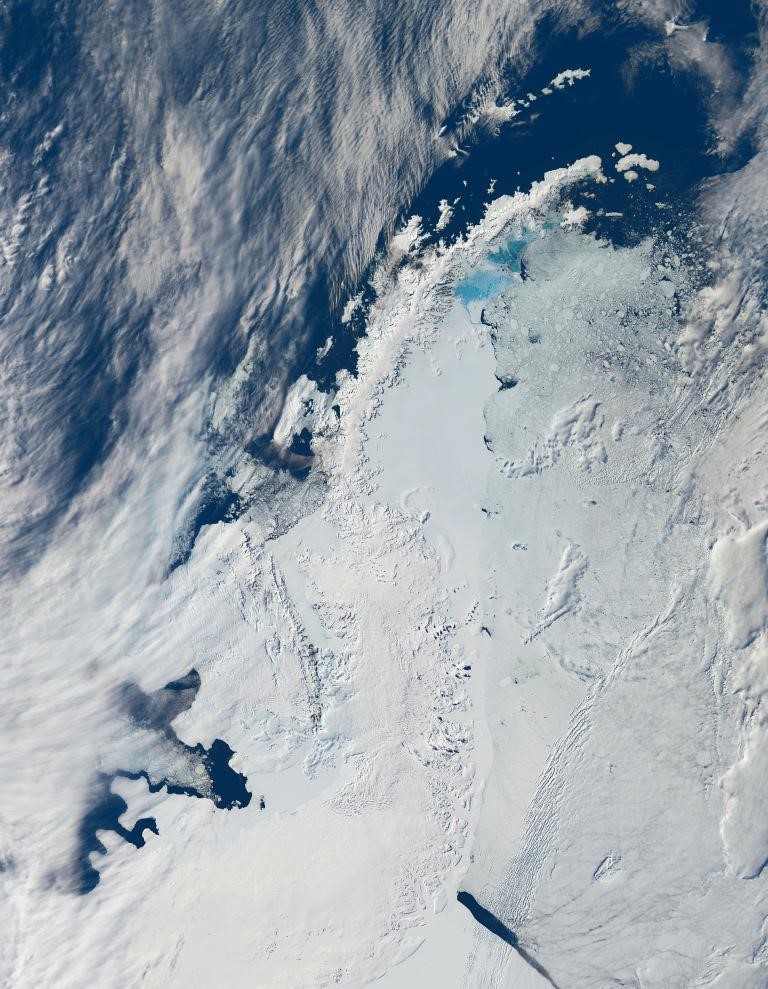

Pine Island Glacier and Antarctic Peninsula, western Antarctica – Satellite Image (2016)

This image shows the Antarctic Peninsula in western Antarctica, with the Pine Island Glacier in the lower left.

The Pine Island Glacier, one the largest glaciers in western Antarctica, is the fastest thinning glacier in Antarctica, responsible for some 25% of Antarctica’s ice loss. It loses an extraordinary 45 billion tonnes of ice to the ocean each year — equivalent to 1 millimetre of global sea level rise every eight years. The ice loss rate is alarmingly accelerating. The single glacier contains about 52 centimetres of potential global sea level rise and is thought to be in the process of unstable retreat.

Larsen C, western Antarctica – Satellite Image (2013)

In July 2017, a giant iceberg, known as A68 and measuring 5,800 square kilometres in size, broke free from Larsen C ice field in western Antarctica. (For comparison, Hong Kong Island is 80.5 square kilometres in size) It is one of the largest icebergs ever recorded. This image is a retrospect of how Larsen C looked like in 2013 — a large rift had already been developed (centre of image).

A collection of multimedia-enhanced and interactive modules to educate users on the impact of climate change memorably and enjoyably. The second collection in the series, ‘Climate Change and Me’, consists of seven modules. They reveal how human activities and climate change are closely interlinked and promote important green concepts such as clean energy, a low-carbon lifestyle and sustainable development. Schools or organizations interested in hosting the exhibition may click here for further details.

Consulate General of France in Hong Kong & Macau

December 2016

| (852) 3943 9632 | ||

| mocc@cuhk.edu.hk | ||

| Yasumoto International Academic Park 8/F The Chinese University of Hong Kong Shatin, NT, Hong Kong |

||

The MoCC Ambassadorship recognizes and provides financial support for outstanding CUHK students who wish to intern in the MoCC to raise climate change awareness and promote sustainability on and beyond campus. MoCC Ambassadors undergo knowledge training in climate change, sustainability and museum operations.

Each MoCC Ambassador is required to pursue, under supervision, experiential learning that carries educational benefits for the Ambassador and are relevant to the MoCC’s operational and outreach activities.

Details of the requirements and financial support of the MoCC Ambassadorship are outlined in the programme flyer. When the students graduate from the ambassadorship, each of them will be awarded a certificate of completion. The ambassadorship may be renewed for another academic year upon demonstration of excellent performance and the availability of funding.

Applications are open to all undergraduate and postgraduate students of CUHK. Students in related fields (major or minor), such as sustainable development, earth system science, museum studies, geography, energy and environmental engineering, environmental science, anthropology or those who have a track record in participating in environmental services, may be given priority.

Interested students are requested to complete the online application form by 11:59 pm, 7 January 2021.

Shortlisted applicants will be invited to attend a selection interview to be held on 14 or 15 January 2021.

The MoCC Ambassadors are required to:

Deadline for Application

7 January 2021 (Thursday)

Selection Interview

14 or 15 January 2021 (Thursday or Friday)

Knowledge Training (Tentative)

Online sessions (1:30pm–6:00pm)

Onsite session (TBC)

Dry run of tour, 4 hours

Monthly Meetings

First Friday afternoon of each month:

Questions are welcome and should be directed to Ms Samantha Chui on 3943 3012 or by email at samanthachui@cuhk.edu.hk.

The MoCC Ambassadorship recognizes and provides financial support for outstanding CUHK students who would like to become active ambassadors to call for climate action and promote sustainability on and off the CUHK campus. MoCC Ambassadors undergo knowledge training in climate change, sustainability and museum operations.

Upon completion of the training, each MoCC Ambassador is required to intern at the MoCC to pursue, under supervision, experiential learning that has educational benefits for the Ambassador and is relevant to the MoCC’s operational and outreach activities.

|

Applications are open to all undergraduate and postgraduate students of CUHK.

Interested students should complete the online application form by 11:59 pm on 19 September 2025(Friday).

Shortlisted applicants will be invited to attend a selection interview to be held between 18 and 19 September 2025 (Wednesday to Friday) or 25 and 26 September 2025 (Wednesday to Friday)

Application Deadline

19 September 2025 (Friday), 11:59 pm

Selection Interview

18 September to 19 September 2025 (Thursday to Friday) or 25 September to 26 September 2025 (Thursday to Friday)

Training Courses (tentative)

4 and 11 October 2025 (Saturday)

Assessment

Rehearsal Tour and Practice Tour (2 hours per session)

Late October (exact date to be confirmed)

Monthly Meetings

First Friday afternoon of each month (or the next Friday in case of a public holiday or inclement weather)

Please contact Jayson Chan at 3943 0817 or email jaysonchan@cuhk.edu.hk

|

Hong Kong produces over 15,000 tonnes of municipal solid waste per day, which includes 2,500 tonnes of waste plastics. Plastics are everywhere in our life as they are cheap, lightweight and durable. However, upon decomposition to microplastics, they can infiltrate into our water, air, soil, etc., posing severe threats to the environment and ecology. In Spring 2022, scientists announced they have found microplastics in human blood for the first time. In recent years, countries have come to recognize the importance of responsible consumption and going plastic-free. The practices of reducing the use of plastic materials, especially single-use plastic products, and using other alternatives have been explored and adopted. The Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development Office (SRSDO) of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) is pleased to offer the ‘Design Thinking Summer 2022: Responsible Consumption x Sustainable Development’ programme this Summer. Through trainings and workshops, design thinking and implementation of solutions, the programme educates participants on the importance of SDG 12 – Responsible Consumption and Production, and develops their communication, leadership and organization skills. The programme enables students to unleash their creativity in building a ‘responsible consumption’ campus and community, broaden their horizons and fulfil their responsibilities as global citizens. Programme Details (Chinese version only) |

|

The COVID-19 epidemic has led to a severe economic recession in Hong Kong. According to the ‘Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report 2020’ released by the Hong Kong government, before policy intervention, 1.653 million individuals were living in poverty within the city. The labour market has undergone a significant deterioration, marked by a sharp rise in the annual unemployment rate, which has reached 6.5%—the highest level in 16 years. This has led to a reduction in income or job loss among grassroots, resulting in a concomitant increase in the number of individuals seeking emergency food assistance from the Social Welfare Department, for instance, the number of recipients increased by 20% to 62,000 in 2021. As Hong Kong is ranked as the second highest cost of living city in the world, it raises the question of how the economically disadvantaged can afford basic necessities.

Poverty in Hong Kong is a long-standing issue. As a member of society, it is crucial for secondary school students to gain a comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by grassroots citizens and explore how to contribute to poverty alleviation. The Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development Office of The Chinese University of Hong Kong is pleased to offer the ‘Design Thinking Summer 2023: No Poverty and Zero Hunger’ programme this Summer.

Through training and workshops, design thinking, and short video production, the programme aims to educate participants on the importance of SDG 1 (No Poverty) and SDG 2 (Zero Hunger), develop their sense of empathy, and sharpen their communication, leadership and organization skills. The programme enables students to unleash their creativity in building ‘No Poverty and Zero Hunger’ campuses and communities, broaden their horizons and fulfil their responsibilities as global citizens.

Programme Details (Chinese version only) |

Young adults passionate about climate action often lack the necessary institutional support and visibility in their communities. Many of our exemplary MoCC Alumni, as they embark on a new journey after graduation, are of no exception. The MoCC Scholars initiative was launched during the 10th anniversary of the CUHK Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change to bridge this gap by providing:

To nurture the new generation of climate leaders, the MoCC has set aside resources to support projects initiated by the MoCC Scholars, bringing these young climate enthusiasts’ innovative ideas to life and enabling the creation of meaningful and impactful change towards sustainable development and climate action.

|

|

|

|

The Hong Kong Sign Language videos are developed by the museum and the Centre for Sign Linguistics and Deaf Studies of CUHK.

|

| 1. Introduction of MoCC | ||

| 2. Xue Long/Dr Rebecca Lee Lok-sze | ||

| 3. Seal | ||

| 4. Inuit | ||

| 5. Emperor penguin | ||

| 6. Greenhouse effect and climate change | ||

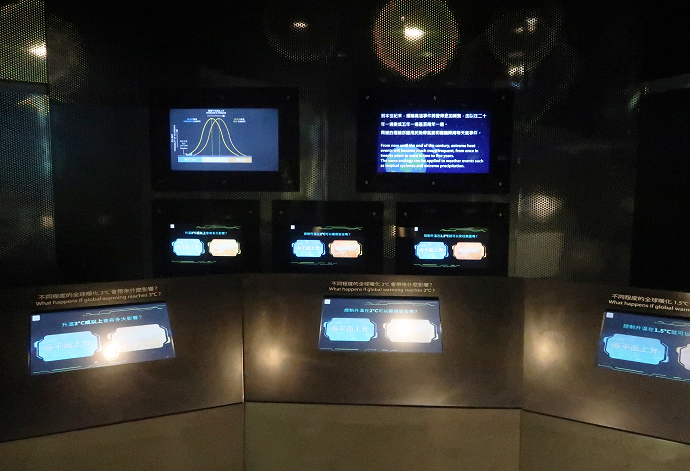

| 7. High/Low carbon emission scenarios | ||

| 8. Urban planning and architecture | ||

| 9. Solar panels | ||

| 10. Carbon footprint from consumption | ||

| 11. Tips for reducing carbon footprint |

|

The audio guides are developed by the museum and the Audio Description Association (Hong Kong).

|

|

1. Introduction of MoCC (Cantonese only) |

|

|

| 2. Xue Long/Dr Rebecca Lee Lok-sze (Cantonese only)* |   |

|

| 3. Seal (Cantonese only)* |  |

|

| 4. Inuit (Cantonese only)* |  |

|

| 5. Emperor penguin (Cantonese only)* |  |

|

|

6. Greenhouse effect and climate change |

|

This exhibit is featured with on-site voice narration. |

| 7. High/Low carbon emission scenarios (Cantonese only) |  |

|

| 8. Urban planning and architecture (Cantonese only)* |  |

|

| 9. Solar panels (Cantonese only) |  |

|

|

10. Carbon footprint from consumption (Cantonese only) |

|

|

| 11. Tips for reducing carbon footprint (Cantonese only) |  |

*Featured with audio descriptions.

In 2024, the MoCC introduced the MoCC Ambassadors Travel Grant to empower outstanding MoCC Ambassadors to expand their horizons and global perspectives through participation in premier international events.

|

|

|

|

| Felix Chan and Carmen Cheng attended the Global Sustainable Development Congress, co-hosted by CUHK and Times Higher Education, in Bangkok, Thailand in June 2024 and shared their journeys in promoting sustainable development. | Katy Dong and Chan Myae Yamon Thwin engaged in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29) held in November 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan. |

The MoCC Ambassadors Travel Grant sponsored two students (Felix Chan and Carmen Cheng) to attend and speak at the Times Higher Education Global Sustainable Development Congress held in June 2024 in Bangkok. Another two students (Katy Dong and Chan Myae Yamon Thwin) took part in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29) held in November 2024 in Baku, Azerbaijan, under the supervision of the mentor, Professor Amos Tai, Deputy Chairperson (Education) of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences.

Eligibility

Applications are open exclusively to active MoCC Ambassadors.

Terms of the Award:

To be eligible to receive the grant, the awardee must:

Post-conference Commitments:

Upon return, the awardee will be expected to:

List of Past Events

| Date | Place | Event | Awardee |

| 10-13 June, 2024 | Bangkok, Thailand | Global Sustainable Development Congress | Felix Chan and Carmen Cheng |

| 11-22 November, 2024 | Baku, Azerbaijan | United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP29) | Katy Dong and Chan Myae Yamon Thwin |

Venue PartnershipAs the world's first museum dedicated to climate change, the MoCC aims to promote climate education through collaboration with various organizations and groups. Located in a beautiful university campus, conveniently near the University MTR station, the MoCC provides unique venues for hosting different types of events. |

||

|

|

||

Themed Exhibition CorridorAvailable for themed exhibitions, with an entrance area that can accommodate approximately 20 to 30 people. Its stunning view of Ma On Shan promenade making it ideal for workshops, small opening ceremonies, and more. |

||

|

|

|

|

SDG GalleryThe multifunctional activity room can seat around 30 people, equipped with built-in computer, wireless presenter, display panel, lectern and wireless microphones, perfect for lectures, workshops, and other events, while enjoying beautiful scenery. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

For inquiries, please email us at mocc@cuhk.edu.hk. |

||

Virtual Tour |

||

|

|

||

CUHK Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change Expert Committee

The Expert Committee is set up by the CUHK Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change Steering Committee to offer expert advice to the Museum on scientific matters, work areas and projects.

(Names are listed in alphabetical order)

| Convenor | Professor Amos Tai, Deputy Chair (Education) of the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, CUHK | ||

|

Members |

Professor Emily Chan, Director, Collaborating Centre for Oxford University and CUHK for Disaster and Medical Humanitarian Response and, Director, Centre for Global Health, CUHK | ||

| Ms Eliza Chan, Chief Experimental Officer, Hong Kong Observatory | |||

| Professor Apple Chui, Research Assistant Professor, School of Life Sciences, CUHK | |||

| Professor Ho Kin Chung, Founding Chairman and Director, Polar Research Institute of Hong Kong | |||

| Professor Jerome Hui, Programme Director, Biology Programme, CUHK | |||

| Professor Morris Jong, Director, Centre for Learning Sciences and Technologies, CUHK | |||

| Mr Edwin Lau, Founder and Executive Director, The Green Earth | |||

| Professor Harry Lee, Associate Professor, Department of Geography and Resource Management, CUHK | |||

| Professor Liu Lin, Associate Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences CUHK | |||

| Dr George Ma, Head, Learning and Engagement, Hong Kong Palace Museum | |||

| Professor Francis Tam, Associate Professor, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, CUHK | |||

| Dr Alvin Tang, Lecturer, School of Life Sciences, CUHK | |||

| Dr Debbie Tsang, Science Officer, Seascape Belgium | |||

| Professor Lisa Wan, Associate Professor, School of Hotel and Tourism Management, CUHK | |||

| Professor Xu Yuan, Associate Professor, Department of Geography and Resource Management, CUHK | |||

| Dr William Yu, Chief Executive Officer, World Green Organisation | |||

| Secretary | Dr Felix Leung, Head of Climate Education and Action, Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development Office, CUHK |

||

Terms of Reference

| 1. |

To provide scientific/expert advice and expertise in specified disciplines for the MoCC’s development and delivery of new exhibitions, educational programmes and outreach activities, and maintenance of collections. |

| 2. |

To assess and evaluate the contents of the MoCC’s exhibitions and educational materials. |

| 3. |

To provide scientific/expert advice to the MoCC in response to queries from the press, other authorities and at its own initiative if it has identified an issue of concern. |

| 4. |

To advise the MoCC on opportunities to improve the impact, focus and quality of its exhibitions and education. |

CUHK Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change Steering Committee

Composition

| Chairperson | |||||||||||

| Appointed by the Vice-Chancellor | Professor Nick Rawlins Pro-Vice-Chancellor / Vice-President |

||||||||||

| Members | |||||||||||

| External members who are experts in climate change or sustainability | Mr Toby Lau Network Coordinator, SDSN Youth Hong Kong |

||||||||||

| Mr Arthur Lee Commissioner for Climate Change, Environment and Ecology Bureau |

|||||||||||

| Dr Rebecca Lee Founder, Polar Museum Foundation |

|||||||||||

| Dr Connie Ng Head of Marine Discovery Centre, Hong Kong Maritime Museum |

|||||||||||

| Faculty members from relevant research and academic units | Professor Hon-ming Lam Director, Institute of Environment, Energy and Sustainability |

||||||||||

| Professor Amos Tai Deputy Chair (Education), Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences |

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

| Secretary | |||||||||||

|

Nominated by the Social Responsibility and Sustainable Development Office |

Dr Felix Leung |

||||||||||

Terms of Reference

| 1. |

To set direction and strategies for the Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change. |

| 2. |

To endorse plans for the museum’s operations in accordance with set direction and strategies. |

| 3. |

To guide the identification, mobilization and engagement of strategic partners and benefactors for the successful implementation of the museum’s initiatives and projects. |

| 4. |

To monitor and evaluate the results and impact of the museum’s initiatives and projects. |

|

|

The Chinese University of Hong Kong and The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charities Trust have joined hands to co-host the Hong Kong chapter of the United Nations Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN). SDSN Hong Kong seeks to mobilize expertise, information and resources from different sectors to address the most pressing environmental, social and economic issues in Hong Kong and advance sustainable development.

Since its inception in early 2018, SDSN Hong Kong has led, supported and participated in a wide range of activities that address some of these challenges in sustainable development and support the implementation of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in Hong Kong and beyond. The network intends to identify various means of collaboration with local and international experts in sustainable development, including researchers, social entrepreneurs, philanthropists, technological experts, government officials and key opinion leaders, in order to pursue sustainability solutions.

In December 2018, SDSN Youth Hong Kong was launched to raise awareness among young people in Hong Kong of the 17 SDGs, to allow them to exchange ideas with experts, and to encourage them to champion the cause of sustainable development by proposing innovative solutions to the many environmental challenges faced by Hong Kong.

SDSN Hong Kong – CUHK Secretariat

Cecilia Lam, Chief Sustainability Officer, The Chinese University of Hong Kong

Ada Chan, PhD, Network Manager

Also Co-Secretary, SDSN Hong Kong Leadership Council, and Co-Secretary, SDSN Hong Kong Executive Committee

Toby Lau, Youth Network Coordinator

Email: sdsn@cuhk.edu.hk

Website: https://www.sdsn-hk.org

Waste is the third largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Hong Kong. The daily domestic waste generation rate per capita of Hong Kong is 1.36 kg, which is the highest compared to neighbouring cities at a similar level of development: 1.00 kg in Taipei City, 0.95 kg in Seoul City and 0.77 kg in Metro Tokyo (Environment Bureau, Hong Kong Blueprint for Sustainable Use of Resources 2013–2022). Waste – as well as waste reduction – is everyone’s responsibility.

The Waste Reduction Project is the first-ever school-based waste-charging simulation project, which aims to increase the school sector’s awareness of Hong Kong’s waste problem and educate school members on sustainable waste management (waste reduction, separation and recycling). We plan to invite 24 secondary schools to participate in the project, who will examine their waste generation, identify ways of achieving ‘zero waste’, take action to reduce waste and, most importantly, promote the action to the students’ households and the communities. Through the engagement infrastructure created by the project, the students – our future green leaders – will spread the message of ‘waste less, save more’ to households and communities, inspiring more positive action to respond to the impending introduction of a quantity-based municipal solid waste charging system.

| Round | Waste measurement (baseline period) |

Workshops and visits organized by the Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change | Waste measurement (waste reduction period) |

| Round 1 | November – December 2017 | December 2017 – April 2018 | January – April 2018 |

| Round 2 | March – April 2018 | May – December 2018 | September – December 2018 |

| Round 3 | November – December 2018 | December 2018 – April 2019 | January – April 2019 |

| Round 4 | March – April 2019 | May – December 2019 | September – December 2019 |

| Round 5 | November – December 2019 | December 2019 – April 2020 | January – April 2020 |

Award Winning Schools

| Outstanding Award |

Round 1 | Hon Wah College | |

| Tack Ching Girls' Secondary School | |||

| TWGHs Kwok Yat Wai College | |||

| Round 2 | N.T. Heung Yee Kuk Yuen Long District Secondary School | ||

| Tin Shui Wai Government Secondary School | |||

| United Christian College (Kowloon East) | |||

| Round 3 | Qualied College | ||

| S.K.H. Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School | |||

| Shun Tak Fraternal Association Leung Kau Kui College | |||

| Improvement Award |

Round 1 | Ho Yu College and Primary School (Sponsored by Sik Sik Yuen) | |

| Tack Ching Girls' Secondary School | |||

| TWGHs Kwok Yat Wai College | |||

| Round 2 | Lok Sin Tong Yu Kan Hing Secondary School | ||

| N.T. Heung Yee Kuk Yuen Long District Secondary School | |||

| Tin Shui Wai Government Secondary School | |||

| Round 3 | Chong Gene Hang College | ||

| Lingnan Secondary School | |||

| S.K.H. Tang Shiu Kin Secondary School | |||

In May 2013, the Environment Bureau of the HKSAR Government published Hong Kong Blueprint for Sustainable Use of Resources 2013–2022 (http://www.enb.gov.hk/en/files/WastePlan-E.pdf), which analyses the challenges and opportunities of waste management in Hong Kong, and maps out a comprehensive strategy, targets, policies and action plans up to the year 2022 for tackling the waste crisis.

According to the Zero Waste International Alliance, ‘Zero Waste is a goal that is ethical, economical, efficient and visionary, to guide people in changing their lifestyles and practices to emulate sustainable natural cycles, where all discarded materials are designed to become resources for others to use. Implementing Zero Waste will eliminate all discharges to land, water or air that are a threat to planetary, human, animal or plant health’ (http://zwia.org/standards/zw-definition/).

Introduction

To achieve a better and sustainable future, the United Nations adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015. Hunger and food waste are two major challenges, among others, we face today. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, around 14 percent of food produced globally is lost after harvesting and before reaching the consumers, while approximately 17 percent of food is being wasted at the consumer level. Even so, nearly 10 percent of the world population is still suffering from hunger.

In Hong Kong, one third of the municipal solid waste comes from food waste. Turning the situation around requires a rethink of how we produce, consume, and share food, as well as what constitutes a sustainable lifestyle. In response to the issue, the Jockey Club Museum of Climate Change (MoCC) of The Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) organizes the ‘SDG Ambassadorship: Rethink Food’ programme, with an aim to engage participants in a comprehensive educational programme to explore the notion of food consumption, its related social and environmental issues in Hong Kong, and to develop creative solutions to the problems.

Objectives

Themes

| SDG | Topics |

| SDG 2: Zero hunger | Hunger and food waste |

| Communities that are particularly vulnerable to hunger | |

| Food security and sustainable agriculture | |

| SDG 12: Responsible consumption and production | Food production and consumption |

| Food waste generation and management | |

| Food date labelling |

Programme components

(Please refer to programme details (Chinese version only))

Target participants

S3 – S6 students

Quota

8 schools. Each participating school shall nominate a team of 4 students to join the programme.

Enrollment

Please complete the online application form (Chinese version only) by 21 December 2022 (Wednesday). Applications are accepted on a first come, first served basis.

Fee

Key dates

| Date | |

| Deadline of application | 21 December 2022 (Wednesday) |

| Training and education activities | 4 February 2023 (Saturday) |

| 11 February 2023 (Saturday) | |

| 18 February 2023 (Saturday) | |

| Food waste reduction campaign | March 2023 to April 2023 |

| Submission of report | April 2023 |

Programme Language

Cantonese supplemented with English

Enquiries

Annie Tong (3943 3975;annietong@cuhk.edu.hk)

【MoCC七周年有獎遊戲】條款及細則

ECF Mobilizing Community Climate Action by Future Museum Curators is an 18-month (2021–2022) school-based community project supported by the Environment and Conservation Fund (ECF). The project capitalizes on the MoCC's experience in climate outreach and advocacy and represents a unique model of experiential and problem-based learning through curating an exhibition that inspires community pro-climate actions. Student participants (our 'Future Curators') will have the opportunity to showcase their works at the MoCC and will reach a larger audience worldwide through our various global partners.

The core component of this project is a comprehensive training programme designed to provide young people with the necessary knowledge and skills to communicate climate change and sustainable development through technology-aided exhibitions.

Various activities are designed to expand the reach and impact of the project, including:

Jennifer Cheng (3943 0817; jennifercheng@cuhk.edu.hk)

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material/event do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Environment and Conservation Fund and the Environmental Campaign Committee.

Through a comprehensive training programme which includes sharing sessions, workshops and field trips, the programme participants (our 'Future Curators') will identify problems of climate change and explore the connections between climate change and the United Nations' (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The training will be provided in multiple modules covering climate change knowledge, basic curation skills and the application of AR technology.

The programme will expose the participants to various aspects of a curator's work, from content research, through description drafting, to exhibit design and development. Under the MoCC's guidance, the participants will work with their teammates to curate their own exhibitions to be staged at their schools and in a virtual gallery. Selected curating teams will co-curate with the museum team a year-end themed exhibition to be staged at the MoCC.

The participants will have the opportunity to showcase their works to a larger worldwide audience through our global partners. These include:

S1 – S6 students

6 to 8 students from each school

The programme will consist of a series of interactive class and practical sessions.

*Participating schools should complete the school seminar, the training sessions and Future Curators' exhibitions.

Drainage system and river biodiversity tour (Online)(5 March and 12 March 2022)

Solar Power Tour (Online)(12 March and 26 March 2022)

Urban Biodiversity talk (Online)(23 April 2022)

|

Please check out the Chinese version

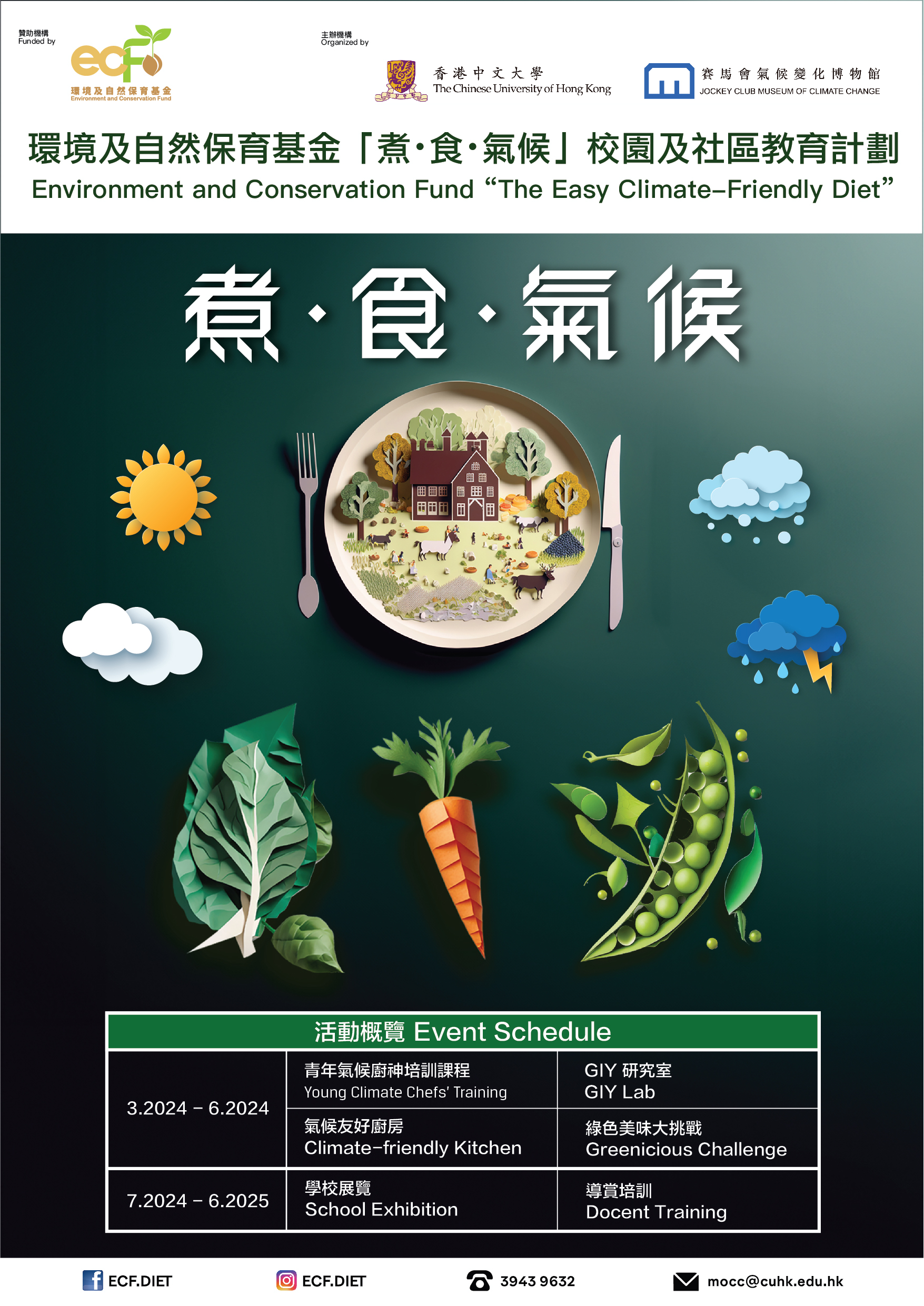

ECF The Easy Climate-Friendly Diet is a 24-month school-based and community engagement project supported by the Environment and Conservation Fund (ECF). Capitalizing on the MoCC’s experience in climate education and outreach, the project promotes a change of behaviour around sustainable diet and food-related habits to reach for a carbon-neutral society.

The core component of this project is to provide an innovative ‘farm-to-table’ education to secondary school students, through a series of experiential learning activities, students to learn the relationship between food system and climate change, so as to inspire others to make more sustainable food choices and opportunities.

Secondary school students

10 secondary schools, each school to nominate four to five students with a total of 40 to 50 participants

Secondary schools in Hong Kong are invited to submit their applications on or before 23 February 2024 (Friday). Applications will be selected on a first-come, first-served basis.

Various activities are designed to expand the reach and impact of the project, including:

Wayne Leung (3943 3975; wayneleung@cuhk.edu.hk)

Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material/event do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, the Environment and Conservation Fund and the Environmental Campaign Committee.

Secondary school students

10 secondary schools, each school to nominate four to five students with a total of 40 to 50 participants

Upon completion of the programme, participants will be awarded an e-certificate issued by The Chinese University of Hong Kong

**Participating schools should complete all the training and activities

More details please check out the Chinese version.

Facebook: @ECF.DIET |

Instagram: @ECF.DIET |

|

Event Highlights |

||

1. ‘Young Climate Chefs’ Training(a) ‘Young Climate Chefs’ Training (16 March 2024) |

||

|

(b) Local Aquaculture Farm Visit (16 March 2024) |

||

|

(c) Local Wet market and Packaging-Free Grocery Store Visit (13 April 2024) |

||

2. GIY Lab (27 April 2024) |

||

3. Climate-Friendly Kitchen (4 and 11 May 2024) |

||

CY Lam’s Webinar on Climate and Diet: Interrelationship between Food and Climate Change |

||

Greenicious Challenge |

||

Reference list:

|

The Mobile MoCC is a multimedia-enhanced and interactive exhibition series designed to educate users on climate change in an enjoyable and memorable way. The first collection in the series, ‘Polar Vision’, includes five exhibit modules which offer a personal virtual experience of climate change from a polar perspective.

The Exhibition Modules are available for loan, at no charge, by schools or organizations. Please submit a request by filling in the online registration form.

The Mobile MoCC is a multimedia-enhanced and interactive exhibition series designed to educate users on climate change in an enjoyable and memorable way. The second collection in the series, ‘Climate Change and Me’, consists of seven exhibit modules. They reveal how human activities and climate change are closely interlinked and promote important green concepts such as clean energy, a low-carbon lifestyle and sustainable development.

The Mobile MoCC is a multimedia-enhanced and interactive exhibition series designed to educate users on climate change in an enjoyable and memorable way. The third collection in the series, ‘Climate Change: Past, Present, Future’, consists of eight exhibit modules which take us on a fascinating journey through time, revealing the importance of climate records and highlighting the current threat of extreme weather. The exhibit modules also explain what climate change means for us and how we can play our part in building a sustainable world.

A well-curated resources hub packed with information on environmental protection, climate change and sustainable development, and designed to inspire the public to take action to combat climate change.

A unique museum has been created.

Consulate General of France in Hong Kong & Macau

December 2016

|

COP29 was the 29th United Nations climate summit, held in Baku, Azerbaijan, from November 11 to 22, 2024. The conference resulted in major agreements to support global climate action. Countries agreed on funding to help developing nations cope with climate impacts and transition to renewable energy. COP29 also established new rules for a UN-supervised system to track and manage international carbon credit trading. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Testimony from MoCC Ambassador Travel Grant awardee |

|

“Till now, my COP29 journey has been completed. I am truly grateful for all the help and support I received. I’m sure that our generation will eventually combat every obstacles we encounter and make the world a better place! “ |

|

Wenjing (Katy) Dong |

|

Post-event sharing |

A well-curated resources hub packed with information on environmental protection, climate change and sustainable development, and designed to inspire the public to take action to combat climate change.